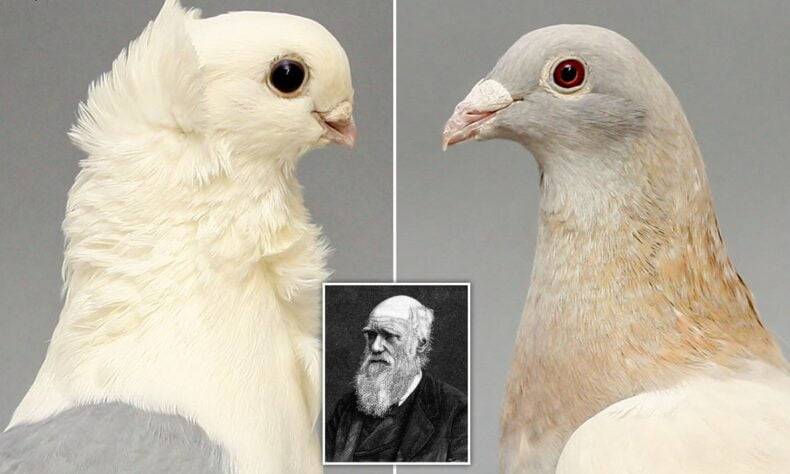

A mutation in the ROR2 gene, which is associated with beak length in domestic pigeons, has an unexpected association with a congenital condition in humans short-beaked bird

Domestic pigeons were a source of fascination for Charles Darwin. He believed they contained the secrets of selection in their beaks, and he was right. Within a single species of domestic pigeons, the 350 or so different varieties have beaks of varied shapes and sizes because they have been freed from the constraints of natural selection (Columba livia). For the most part, short beaks restrict parents from feeding their own young, which is the most remarkable characteristic. Centuries of interbreeding taught early pigeon fanciers that the length of a pigeon’s beak was most likely influenced by a small number of heritable characteristics. Despite this, modern geneticists have been unable to unravel Darwin’s riddle by identifying the molecular machinery responsible for short beaks — at least not until today.

New research conducted by scientists at the University of Utah has discovered that a mutation in the ROR2 gene is associated with beak lengthening in numerous domestic pigeon breeds, according to the findings of a recent study. As an added surprise, mutations in ROR2 have been linked to a human illness known as Robinow syndrome.

Elena Boer, lead author of the paper and a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Utah who completed the research while working as a clinical variant scientist at ARUP Laboratories, said, “Some of the most striking characteristics of Robinow syndrome are the facial features, which include a broad, prominent forehead as well as a short, wide nose and mouth, and are reminiscent of the short-beak phenotype in pigeons.” From a developmental aspect, it makes sense because we know that the ROR2 signalling pathway is critical in the development of the craniofacial complex in vertebrates.

On September 21, 2021, the study will be published in the journal Current Biology.

Gene mapping and the mapping of skulls

The researchers created two pigeons with short and medium beaks; the medium-beaked male was a Racing Homer, a bird bred for speed with a beak length that was comparable to that of the ancient rock pigeon; and the short-beaked female was a Rock Pigeon, a bird bred for size. The Old German Owl, a luxury pigeon breed with a small, squat beak, was the source of the small-beaked female’s appearance.

“Breeders picked this beak solely for its beauty to the point where it is detrimental to the animal’s survival; it would never exist in the wild. As a result, domestic pigeons provide a significant advantage in the search for genes responsible for size disparities “Michael Shapiro, the James E. Talmage Presidential Endowed Chair in Biology at the University of Utah and a senior author on the research, explained his findings. “A central argument of Darwin’s theory of evolution was that natural selection and artificial selection are two different versions of the same process. The size of pigeon beaks played a crucial role in figuring out how it works.”

Children with intermediate-length beaks were born to the parents who had short and medium-length beaks in the first generation of the F1 breeding programme. By mating the F1 birds with one another, the biologists were able to produce F2 grandkids with beaks that ranged in size from large to small, as well as all sizes between. Boer used micro-CT images taken at the University of Utah Preclinical Imaging Core Facility to quantify the diversity in beak size and shape among the 145 F2 individuals studied.

In addition, “the interesting thing about this technology is that it allows us to examine the size and shape of the complete skull,” Boer explained. “It turns out that it’s not just beak length that varies, but that the braincase also changes shape at the same time. short-beaked bird These analyses revealed that variation in beak length within the F2 population was related to real differences in beak length rather than change in total skull or body size,” the researchers said.

Following that, the researchers compared the genomes of the pigeons. They began by identifying DNA sequence variants dispersed throughout the genome using a technique known as quantitative trait loci (QTL) mapping, and then sought to see if those alterations appeared in the chromosomes of the F2 offspring.

‘We discovered that the grandchildren with small beaks shared the same bit of chromosome as their grandfather who had a little beak, which indicated that the piece of chromosome had something to do with small beaks,’ explained Dr. Shapiro. “And it was on the sex chromosome, which was in line with what conventional genetic research had revealed, so we were very enthusiastic about that.”

The full genomic sequences of several distinct pigeon breeds were then compared; 56 pigeons from 31 short-beaked breeds were compared to 121 pigeons from 58 medium- or long-beaked breeds were compared to each other. The investigation revealed that all individuals with short beaks shared the same DNA sequence in a region of the genome that encodes the ROR2 gene, which was previously thought to be unique.

According to Boer, “the fact that we were able to obtain the same strong signal from two distinct techniques was quite exciting and offered an extra degree of evidence that the ROR2 locus was involved.”

It’s hypothesised that the short-beak mutation causes the ROR2 protein to fold in a different way, but the team aims to conduct functional experiments to see whether the mutation has an impact on craniofacial development.

Pigeon aficionados are a special breed.

Darwin was captivated by the tame pigeon, and the allure of the bird continues to captivate the curious to this day. Several of the blood samples that were used by the research team for genome sequencing came from members of the Utah Pigeon Club and the National Pigeon Association, two groups of pigeon enthusiasts who continue to breed pigeons and compete in competitions to demonstrate the striking variation between breeds.

As Shapiro points out, “every single report our lab has published over the previous ten years has relied on their material in some way.” This would not have been possible without the support of the pigeon breeding community.

For More Information Visit : Timez Magazine